VALLEJO – For the first time, the city of Vallejo must establish an action plan for how it’s going to combat sea level rise over the next few decades.

This is part of SB 272, a state bill passed in 2023 that requires that local governments come up with strategies to address flooding hazards caused by climate change. The law applies to all coastal cities that fall under the jurisdiction of the San Francisco Bay Conservation and Development Commission, which has been overseeing shoreline regulations for all nine Bay Area counties since 1965.

The bill also requires that cities incorporate environmental justice principles in their plans by identifying at-risk communities that will be hit by flooding the hardest and struggle to bounce back the most in the event of a massive storm.

To that end, the city is working with environmental organizations like Greenbelt Alliance and Sustainable Solano to host workshops, brainstorm equitable solutions, and collect feedback from the community. The latest working group was held on Nov. 13 at the John F. Kennedy library.

Sea level rise is “a global phenomenon, but the impacts will be felt locally,” said Nate Huntington, a resilience manager with Greenbelt Alliance. “Potential local impacts include damage to buildings, roads, power systems, critical infrastructure, and transportation services that people rely on.”

Sustainable Solano co-executive director Allison Nagel said that the common concerns they’ve heard from residents are how sea level rise might impact their daily lives. “Is it going to keep people from being able to get to work, or being able to get to the grocery store?” Nagel said.

Huntington noted that while the environmental groups will provide guidance to the city, it’s up to the Vallejo City Council to decide whether it wants to adopt their recommendations or not.

“We’ll provide guidance on some of the risks and the potential adaptation solutions, but we can't force the city of Vallejo to change the way it operates or decide how it utilizes land,” said Huntington.

The cities have until January 2034 to submit their adaptation plans to the commission, though they’re strongly encouraged to finish sooner.

Sea levels have been rising globally since the 1880s — a result of humans burning fossil fuels, which creates greenhouse gases that warm the Earth and melt glaciers. Depending on how much governments are able to curb global warming, the California Ocean Protection Council estimates that the Bay Area could experience anywhere from 2-7 feet of sea level rise by 2100.

“If we as a community, a government, and a state really worked to aggressively tackle sea level rise and climate change, then we can see the lower end of sea level rise projections,” explained Mariah Padilla, a Greenbelt Alliance resilience manager for the Sonoma area. “But if we take no action, then we can expect higher levels of sea level rise, which can lead to exacerbated flooding and more intense impacts.”

The latest United Nations report states that the world is currently off-target from keeping global warming at a level that would make those lower sea level rise projections possible.

Protecting all the areas of the Bay area that are vulnerable to flooding will be costly: the Metropolitan Transportation Commission estimated in a 2023 report that it could take around $110 billion, with Solano County requiring a roughly $7 billion investment.

The report acknowledges the high price tag, but it states that inaction could cost the Bay Area even more: $230 billion in property and infrastructure damage if local governments do not build flood mitigation infrastructure like marshes, levees, and seawalls.

“I think the big challenge with a lot of these projects is that they are long-term. They are expensive,” said Nagel. “So different municipalities are going to have to figure out how they can fund those projects.”

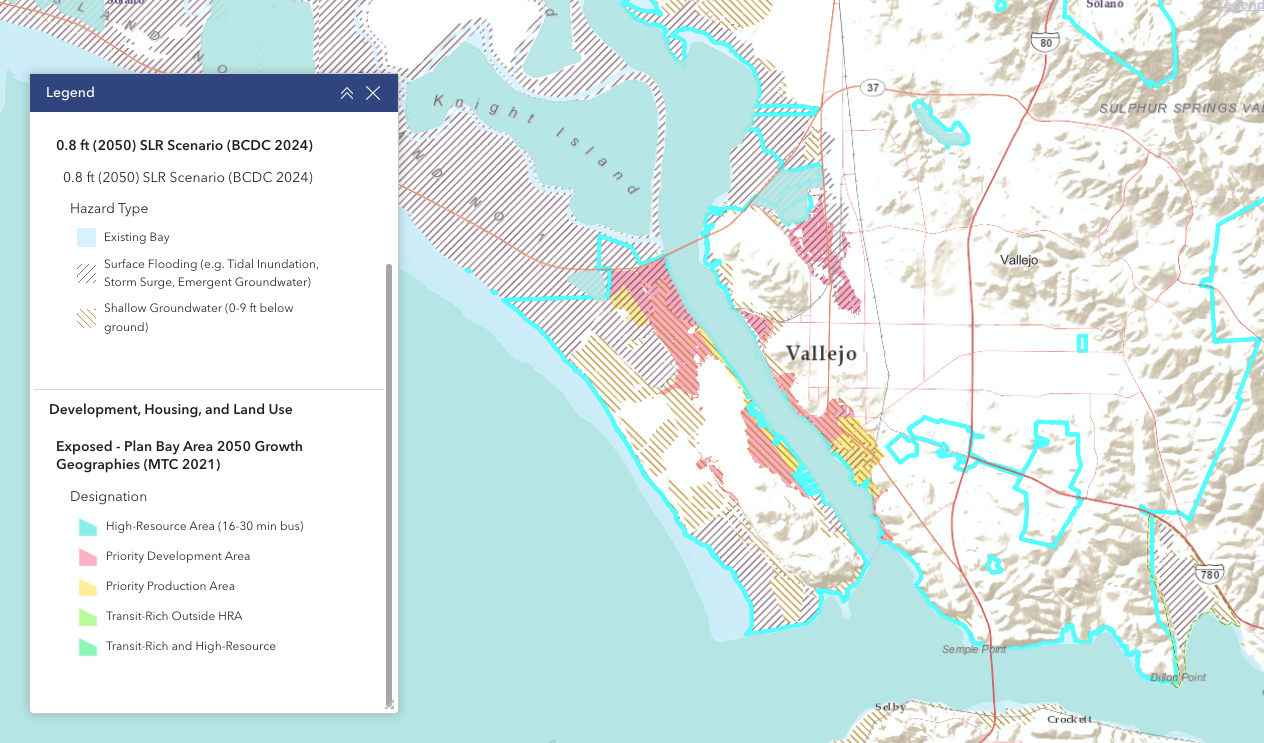

To help cities draft their own plans, the commission created a shoreline adaptation plan for the region in 2024. The regional plan includes a guidance document that directs cities to plan for one foot of sea level rise by 2050 — which the report states is likely — along with several possible scenarios of sea level rise of up to seven feet by 2100.

The commission also has a beta map tool where residents can explore how sea level rise might affect their community. The maps show that in a 2050 scenario of one foot of sea level rise, the entirety of White Slough, large sections of Mare Island, and portions of South Vallejo will be flooded or have groundwater rise, which is when saltwater moves underneath the soil and pushes up fresh water. This is dangerous because it can weaken underground building infrastructures and damage sewer lines — an already significant problem on Mare Island.

Groundwater can also seep into waste sites and spread pollution into the surrounding areas. According to the map, 40% of contaminated sites in Vallejo will be exposed to groundwater in the 2050 scenario. These include the Vallejo Flood and Wastewater facility and shut down gas stations, auto yards, and steel mills in South Vallejo — an area where the community already faces higher rates of air pollution.

Community members at the Nov. 13 meeting said that it’s important to them that the action plan develops realistic, fundable solutions that consider the needs of the most vulnerable in Vallejo. Some pointed out that the flooding of White Slough would mean the displacement of all the unhoused people living there. Another said that some Vallejoans might find it hard to care about sea level rise that’s happening 25 years in the future when they’re concerned about how they can afford food and rent today.

Padilla said they’ll continue to collect feedback from the community, and noted that the project is still in its very early stages. “There’s sort of two phases,” said Padilla. She said that currently Greenbelt Alliance and the other community organizations are meeting with the different cities of Solano County and conducting a vulnerability assessment, which is “just to understand what are the sea level rise impacts and risks that Solano County is facing.”

She said once they have a handle on the issues, the groups will transition into talking about actual adaptation solutions that cities can implement. These can include plans to shore up existing wetlands, changing building codes so that ground floors are taller, or building more affordable housing in the event that residents are displaced as a result of persistent flooding.

The next working group is expected to be in February 2026. Residents interested in attending can sign up for updates at the Solano Bayshore Resiliency website.

There will also be a virtual countywide meeting for the project on Dec. 3 at 6:30 p.m. Sustainable Solano encourages residents to attend to share their concerns and ideas.

“The hope is to have plans in place that really are informed by the priorities of the community,” said Nagel. “We're doing this work to inform what is created for the regional plan, that can then inform the decisions that the cities and the county are making.”

Before you go...

It’s expensive to produce the kind of high-quality journalism we do at the Vallejo Sun. And we rely on reader support so we can keep publishing.

If you enjoy our regular beat reporting, in-depth investigations, and deep-dive podcast episodes, chip in so we can keep doing this work and bringing you the journalism you rely on.

Click here to become a sustaining member of our newsroom.

THE VALLEJO SUN NEWSLETTER

Investigative reporting, regular updates, events and more

- environment

- government

- Vallejo

- SB 272

- San Francisco Bay Conservation and Development Commission

- Greenbelt Alliance

- Sustainable Solano

- Nate Huntington

- Allison Nagel

- White Slough

- Mariah Padilla

Gretchen Smail

Gretchen Smail is a fellow with the California Local News Fellowship program. She grew up in Vallejo and focuses on health and science reporting.

follow me :