VALLEJO – In 2020, as the country grappled with disruptions and closures from the COVID-19 pandemic, a surge of crime came with it. The homicide rate rose by 30% nationally from 2019 to 2020, the largest single-year increase in over a century, according to a Pew Research Study.

In Vallejo, 28 people were murdered in 2020, a 133% increase over 2019 and the city’s deadliest year since 1994.

Five years later, the country’s pandemic-era crime spike has mostly declined. A study by the Council on Criminal Justice found that crime has declined in 42 major American cities, and as of this year, national crime rates are now equivalent or lower than in 2019, the year before the pandemic started.

Vallejo, along with other major Bay Area cities, has also followed this trend. In Vallejo, which has struggled with a highly publicized police staffing shortage for the last two years, most crime categories are at or below their 2019 levels, but homicides remain elevated, according to a Vallejo Sun examination of six years of police data.

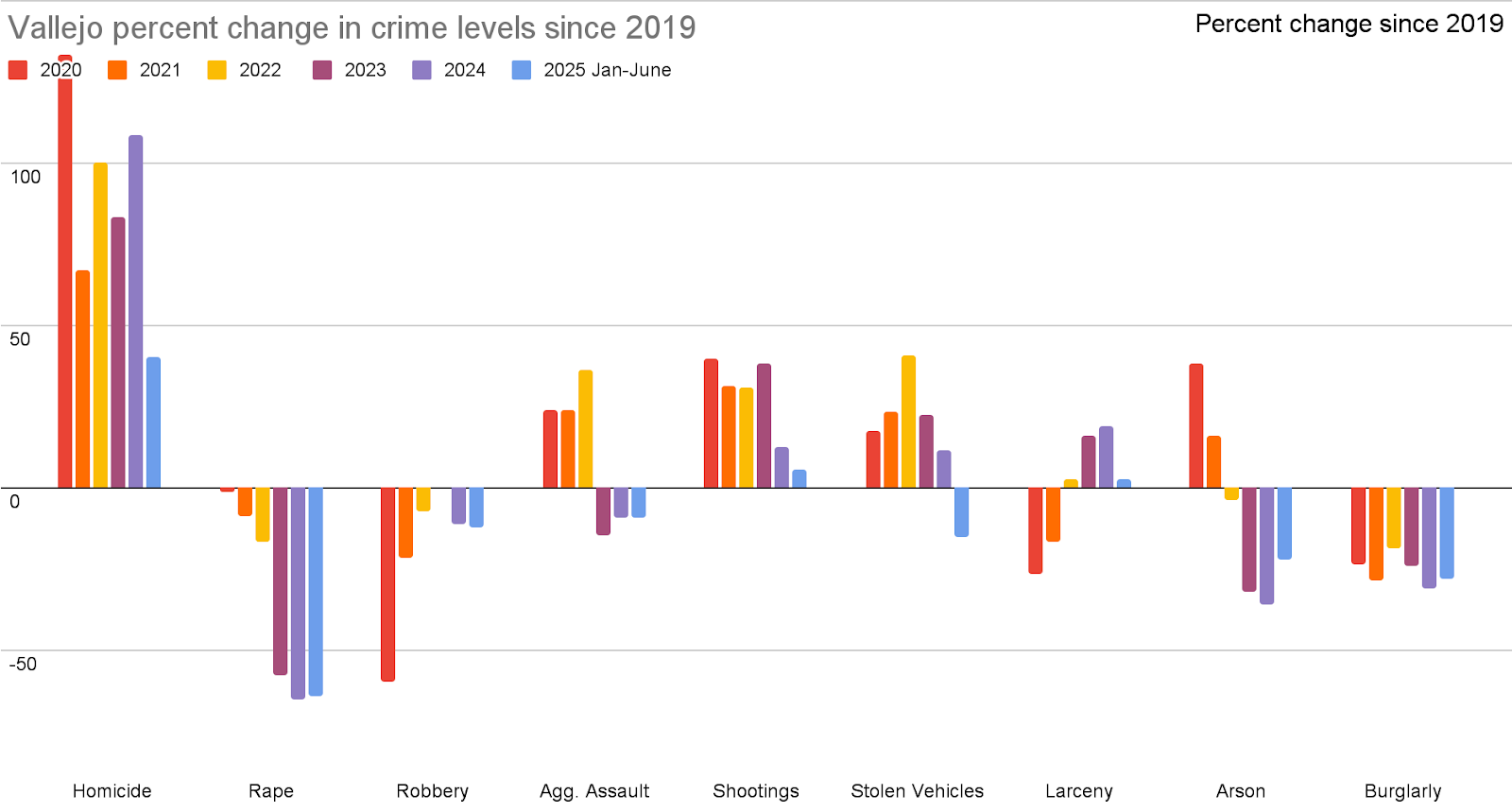

The Vallejo Sun examined nine categories of crime recorded by Vallejo Police to calculate the percent change in crime compared to 2019. Data from January to June were used for 2019 and 2025 in order to compare the first half of this year.

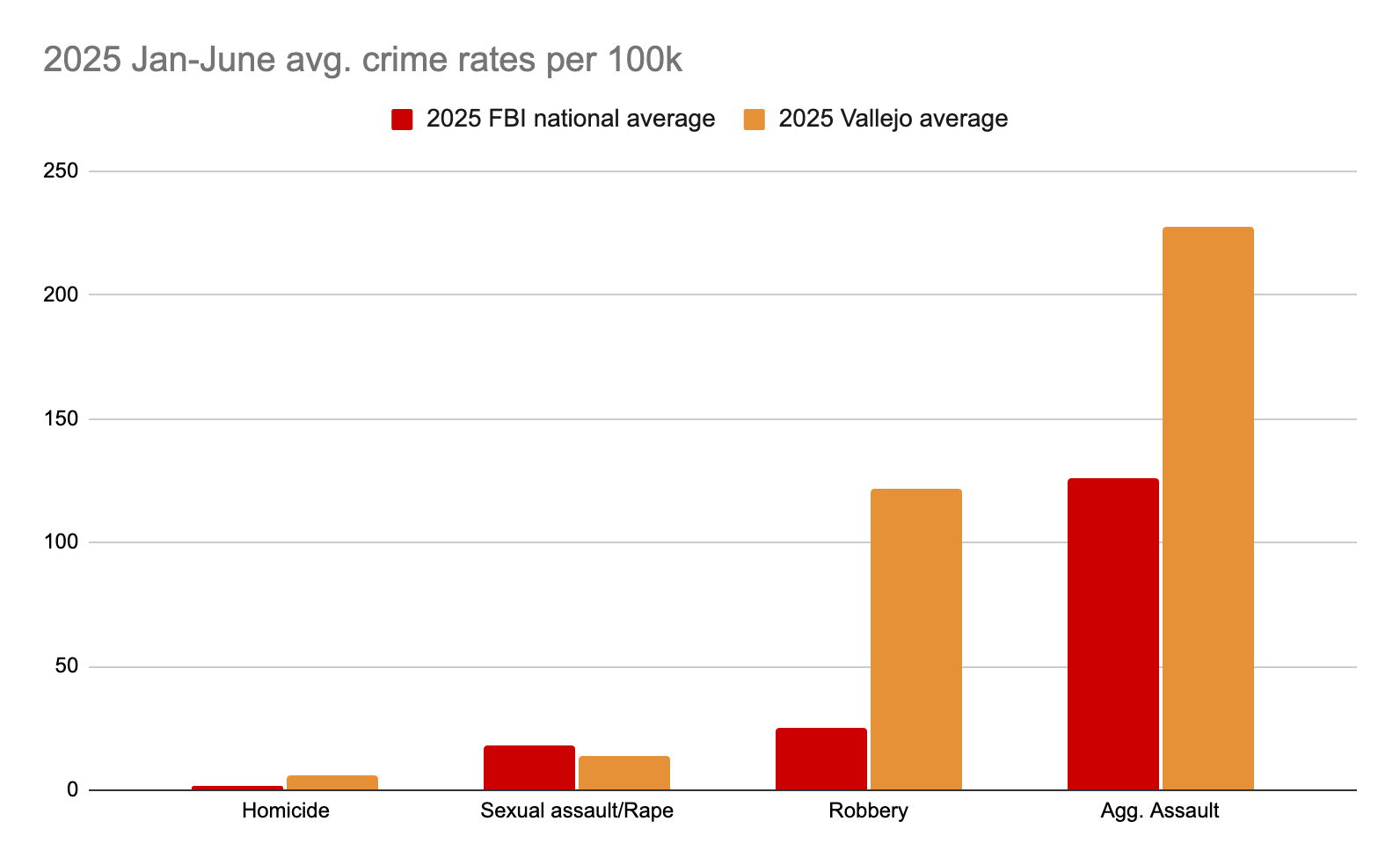

While crime in Vallejo has gone down in the last five years, it remains higher than the national average.

For the first half of this year, robbery in Vallejo was nearly five times the FBI’s national average per capita. For the most part, Vallejo’s crime rate closely resembles crime rates seen in major metropolitan cities significantly larger in size.

The following graph compares violent crime between Vallejo and the national average for the first half of 2025. The Sun took total crimes recorded by the FBI and calculated the crime rates according to the country's population.

Compared to 2019, homicide remains elevated in Vallejo while the number of recorded rapes had the largest decrease. For rape, the change could be in part due to changes in how Vallejo Police defines it, using a legacy definition that has been discontinued by the FBI.

Police spokesperson Sgt. Rashad Hollis said that Vallejo Police recently changed their categorization of rape, having started reporting “rape” and “all other sexual assaults/offenses” as seperate categories.

“Back then, sexual assault and sodomy were all included in rape,” Hollis said. Now, Vallejo police only classify rape when there is penetration of a vagina by a penis, Hollis said

The FBI removed sex-specific criteria from its definition of rape, broadened it to include penetration of any bodily orifice, and changed the focus on “forceful” to “lack of consent,” since 2013.

Hollis said he did not know why Vallejo police changed their practice to deviate from national crime reporting standards.

Experts warn of the statistical reliability of rape reporting under any circumstances. “Crimes like rape or sexual abuse, those are always heavily under-reported,” Carina Gallo, professor of Criminal Justice Studies at San Francisco State University, said in an interview.

But the lingering high level of homicide in Vallejo concerns experts. “A lot of people when they follow crime trends, they actually look at homicide rates because it’s the most accurate," Gallo said.

“That is the crime that has the most corresponding police reports,” Gallo said, “like it's hard to miss a dead person.”

By the end of September of this year, there have been 14 homicides confirmed by the Vallejo Police Department. For comparison, there were 12 homicides for all of 2019. It is probable there will be more before the year ends.

According to the Council on Criminal Justice, homicide nationally in 2025 is 14% lower than in 2019. Yet, in Vallejo, the January-June 2025 homicide rate remained 40% higher compared to the same six-month period in 2019.

Council on Criminal Justice senior research specialist Ernesto Lopez said in an interview that high levels of crime usually accompany high levels of homicide. “Any sort of aggravated assault, any sort of violent confrontation, the fact that that confrontation occurred, increases the likelihood that it could end in a homicide,” Lopez said. On a national level, “some of what explains the decrease in homicide is just the decrease in crime.”

What’s more, Vallejo is statistically anomalous for a city of roughly 124,000 residents. “Usually cities around that size are not seeing homicide rates that high. Typically, once you start getting below a quarter million people, in most cases, the homicide rate does drop notably,” Lopez said. “There's going to be some other reasons that are explaining those trends.”

“[Vallejo homicide rates are] higher if you look at the national average, but it's not as high as Baltimore or St. Louis or Chicago,” Lopez said.

For comparison, Oakland, with a population of 444,000, has higher crime rates per capita than Vallejo, other than for arsons and shootings. This is to be expected to the extent that Oakland is significantly larger and more densely populated than Vallejo.

Richmond, with a population of 115,000, has a significantly lower homicide rate than Vallejo’s. Richmond this year so far has had three homicides, which occurred in July and September. Last year it had 11.

UC Berkeley professor of African American Studies Nikki Jones said in an interview that she is concerned about the potential for returning high crime rates. “The conditions under which relational conflict is exacerbated are about to increase again,” said Jones, “given the kind of dramatic shifts in the economy.”

Crime rates are worsened by social upheaval. Jones warns that worsening economic conditions and the gutting of social services will exacerbate crime, a return to a similar set of conditions that occurred during the pandemic. “When civil law is weak, street justice comes to the fore,” she said.

Why the crime trends in neighboring cities vary so much is not a simple answer. Jones said that police practices alone cannot explain a rise or decrease in crime rates. “There are cities where violent crime has gone down, even with police departments that are understaffed,” she said.

Vallejo declared a public safety emergency in July 2023 because of critical police staffing levels, which has led to an increase in response times.

“Police response time or emergency response time can be the difference between an aggravated assault and a homicide,” Jones said.

However, Jones, whose expertise is on Black people’s experiences in the legal system, said that community-based violence reduction programs can also have significant impacts on the areas where violence is most present.

In 2020, the most murderous year in recent Vallejo history, 71% of homicide victims were Black, despite making up 18% of Vallejo’s population. Most of the shootings that year occurred in North Vallejo and the vast majority of violent crime as a whole is concentrated on the west side of I-80.

“How do we develop an ecosystem of safety in a community where violence has been chronic over a period of years?” Jones said.

“Some people look to law enforcement,” she said. “We should know from history that that's not going to be enough.”

Jones stressed the importance of having programs that offer positive outlets for young people in communities impacted by violent crime. This year, Vallejo resurrected its Late Night Basketball summer program with an aim to have young people playing basketball late at night instead of out in the streets.

Jones said that when someone feels like they are left to fend for themselves it can lead to choices that increase one's likelihood of becoming both a victim or a perpetrator. Vallejo police’s history of misconduct, allegations of excessive force and long response times, have left many Vallejoans distrustful. While Vallejo police have not fatally shot anyone in the past five years, in 2012 they killed six people in a single year, making up 30% of that year's homicide rate.

“You have young people making decisions like, I gotta carry a gun with me. So if you have a gun with you and something pops off, you are more likely to use a gun, right?” Jones said. “And then you become a shooter, or you get shot, or both. And so that's been the cycle that we have.”

“The stakes are high, the violence is real,” Jones said. “Those don't encourage the kinds of conditions where people can think clearly about what to do next when they find themselves in a conflict situation.”

Richmond and Oakland both have long standing programs called Ceasefire that target those believed to be responsible for most shootings and homicides.

“Those who are most likely to be victims or perpetrators of violence. They call those people in and they say, look, you got to stop shooting each other. If you don't, the heavy hand of the criminal justice system is going to come down on your head,” said Jones. “That has been shown to reduce gun violence.”

Vallejo is working to onboard more police officers and arranged an $11 million contract with Solano County to bring in sheriff deputies to patrol Vallejo beginning Jan. 1.

But Jones warns that police cannot be the only answer. “There has to be an ‘and.’ You have to have this kind of menu of other resources available, particularly for young people who have suffered through a lot, through the pandemic.”

“It becomes really important to have these conversations about how do we develop an ecosystem of safety in a community where violence has been chronic over a period of years,” said Jones.

“Like Tupac said, I see death around the corner, and it's real, like kids see death around the corner on their block. And it has to be terrifying, and I know it to be terrifying,” Jones said. “It is terrifying to have to figure out a way to stay safe under those conditions.”

Editor's note: This story has been updated to correct the population of Richmond, California.

Before you go...

It’s expensive to produce the kind of high-quality journalism we do at the Vallejo Sun. And we rely on reader support so we can keep publishing.

If you enjoy our regular beat reporting, in-depth investigations, and deep-dive podcast episodes, chip in so we can keep doing this work and bringing you the journalism you rely on.

Click here to become a sustaining member of our newsroom.

THE VALLEJO SUN NEWSLETTER

Investigative reporting, regular updates, events and more

- crime

- policing

- Vallejo

- Vallejo Police Department

- COVID-19

- Council on Criminal Justice

- Ceasefire

- Rashad Hollis

- FBI

- Carina Gallo

- Ernesto Lopez

- Nikki Jones

Sebastien K. Bridonneau

Sebastien Bridonneau is a Vallejo-based journalist and UC Berkeley graduate. He spent six months in Mexico City investigating violence against journalists, earning a UC award for his work.